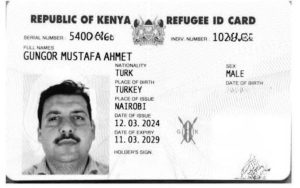

The arrest of a Turkish national and his family in Nairobi has ignited a fierce debate at the intersection of human rights, international diplomacy, and Kenya’s own obligations under domestic and international law. At the centre of the storm is Mustafa Güngör, whose detention—alongside his wife, children and in-laws—has drawn sharp condemnation from Amnesty International Kenya and renewed scrutiny of Kenya’s past cooperation with Türkiye on sensitive extradition and repatriation cases.

As pressure mounts behind closed doors, questions are emerging: Was due process followed? Is Kenya at risk of violating the principle of non-refoulement? And how much influence do bilateral relations carry when weighed against human rights law?

According to Amnesty International Kenya, Güngör’s arrest was neither accidental nor routine. The rights group says it has “reliably learnt” that the detention followed a Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) request initiated by Turkish authorities and transmitted through Kenya’s Office of the Attorney General.

That detail is critical. MLAs are legal cooperation tools designed to assist investigations and prosecutions—but they are not extradition orders. Legal experts warn that using such requests as a basis for arrest and possible deportation raises serious red flags, especially where asylum, refugee protection, or risk of torture is involved.

“This appears to be a classic case of legal cooperation sliding into forced return,” said a Nairobi-based international law scholar who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter. “Kenya must separate diplomatic goodwill from its binding human rights obligations.”

At the heart of Amnesty’s alarm is the principle of non-refoulement, a cornerstone of international refugee and human rights law. It prohibits states from returning individuals to countries where they face a real risk of torture, persecution, or other serious human rights violations.

Amnesty warns that Güngör and his family could face arbitrary detention, torture or ill-treatment if returned to Türkiye—concerns that echo long-standing reports by international watchdogs on the treatment of individuals accused of political dissent or alleged links to outlawed movements.

Kenya is bound by:

The 1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Against Torture

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

Its own Constitution of Kenya, 2010, which explicitly prohibits torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Any deportation in violation of these frameworks could place Kenya in breach of international law.

Echoes of 2024: A Troubling Precedent

The current case is unfolding against the backdrop of a controversial episode in October 2024, when four Turkish nationals—described by rights groups as refugees—were repatriated after being abducted by armed men.

At the time, Foreign Affairs Principal Secretary Korir Sing’oei confirmed the repatriation, citing “robust historical and strategic relations” between Kenya and Türkiye. While the government said it had received assurances that the individuals would be treated with dignity, rights organisations criticised the secrecy surrounding the operation and the lack of judicial transparency.

That episode now looms large.

“Once is an anomaly. Twice becomes a pattern,” said a senior official at a Nairobi-based civil society organisation. “The fear is that Kenya is slowly normalising returns that should never happen under international law.”

Kenya and Türkiye have deepened diplomatic, trade and security ties over the last decade. Turkish investments span infrastructure, education and manufacturing, while cooperation agreements cover security and legal assistance.

But critics argue that bilateral relations cannot override human rights protections.

Leave a Reply